September 17, 2011

How It’s Made: Incubate

This post is a long one, but I promise that the full recording is at the end…

I used to have a mild fascination with the show “How It’s Made.” The theme song, the background music, and the completely useless explanation of How things are Made. It’ll be a segment like “How It’s Made: Vacuum Cleaners,” and while the cheery music plays, the voiceover will say something like, “First, the frame is assembled. Next, a worker attaches the motor, which was assembled at another factory. Wires are connected, and the vacuum is complete! And that’s one vacuum that really… sucks!” (There’s always a bad pun at the end.)

Wait, wait – what the hell?! This isn’t “How it’s Made” so much as “How it’s Assembled.” I don’t think I have ever seen a single segment on the show that effectively explained how anything was made, top-to-bottom, except a segment I saw about pencils (the non-mechanical kind). The show, while charming, is useless. This blog entry will be the same, minus the charm.

I’ve been reading a lot of composer David Rakowski’s excellent blog lately. Somehow I didn’t discover it until last week, but I now read a post nightly. Rakowski lives in the Boston area, teaches at Brandeis, and has won just about every fancy composition prize. He wrote “Ten of a Kind” for the US Marine Band a few years ago, and it is possibly the most technically difficult band work I’ve ever heard. (Not positive, but I’m pretty sure it’s even harder than Steve Bryant’s Concerto for Wind Ensemble.) Rakowski’s music is heavily chromatic and sometimes thorny, but never to the point of bleepy-bloopy. It’s a harmonic language that I like a lot, as it’s a little outside of what I could ever actually do, and that makes it fun. Challenging without being incomprehensible is a wonderful balance.

At my request, Doctor Dave (that’s what I call him, behind his back) emailed me a few MIDI files of some of his piano etudes, so I could throw them at the new Disklavier. One of the etudes, “Wiggle Room,” is inspired by Bach’s Prelude in c minor from book 1 of one of The Well Tempered Clavier. If you don’t know that Bach prelude, here’s a recording of it, as sequenced (with a joystick, I might add) into my Commodore 64 when I was 13 years old. Prepare to be wowed.

[ca_audio url=”https://www.johnmackey.com/audio/Bach-Prelude-Sidplayer.mp3″ width=”500″ height=”27″ css_class=”codeart-google-mp3-player”]

Being inspired by Bach, Rakowski’s etude goes so far as to contain no dynamics, articulations, or pedal markings, leaving those decisions up to the performer. (I can not imagine ever ceding that much control, unless I was allowed to restrict those performer-determined dynamics to a range between forte and fortississississississimo.) Here’s a video of my Disklavier performing the etude, with my own dynamics, articulations, and pedaling picked and added to the Finale file. (This was a lot of fun. Made me wish I could play an instrument in real time.)

Rakowski’s blog has some real gems. You should read “The Means Justifies the Ending.” First, though, you should read a personal favorite, called “Talk the Talk,” about the different ways that a composer needs to be able to talk about their music (to a concert audience, to a composition student, etc.). I was really struck by this paragraph:

Hard as it is to talk about music — it’s famously like dancing about architecture — talking about your own music is harder still. Not least because most of what a composer does — shut him/herself up in a small private place and spin out notes for private and convoluted reasons — isn’t really that interesting, except at the moment, to the composer. Moi-même, I probably find the act of writing pretty intense, since I almost never remember anything about actually writing it down — not even of writing Thickly Settled, finished just yesterday. I remember intentions and ways of thinking, but I completely forget everything about the actual act of writing it down. So how can I say anything intelligent about my own music if all I remember is intentions and not the actual act of composition?

I’m exactly the same way. Are there exceptions to this? Do composers ever remember the actual act of writing the notes? Maybe if the notes are pre-determined by some sort of system like a tone row, but if you’re working intensely on a piece and that work consists of intense decision after decision (see NY Times article about Decision Fatigue), selecting the notes and the rhythms and the dynamics for every moment, is there enough brain power left to remember those moments? In my experience (and apparently Rakowski’s), the answer is no.

It’s certainly true for my recently-completed percussion concerto, “Drum Music.” But let’s see if I can remember enough of the process for one movement – the second movement, “Incubate.” By looking at various versions of the piece, I can sort of remember a lot of it, even details like specific notes aren’t really there.

The initial idea: I wanted it to be extremely still. That would be unexpected in a percussion concerto, I thought. Could I also make it emotional? Could I make it sound almost haunted, but without using sound effects? Those were the questions I wanted to try to answer.

Okay, first thing’s first: it’s slow. But it’s part of a percussion concerto, so how would I accomplish sustained notes? First thought: rolled marimba. You can roll a marimba and sustain indefinitely, so that’s the best idea. But it’s not. It’s just the most obvious idea. Because we have to start somewhere, we’ll go with it.

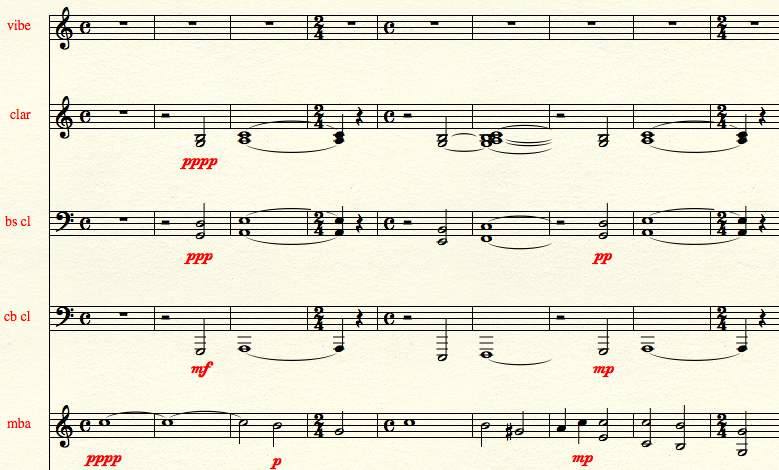

Okay, so we have rolled marimba. I got an idea for a very, very simple chord progression (this is me we’re talking about; I only know about 2 chords) – I have no memory of thinking of the progression itself – and I decided pretty quickly (based on what I entered into the first Finale file for the piece – there were 19 different files for this movement by the time I was done) that the progression would be in low clarinets.

There’s a sustained C in the marimba (bottom staff), not making it clear what key we’re in, and then the clarinets come in with a G major chord, making the marimba note a (mildly) dissonant note. The clarinets then move up a whole step (as any music theory class will tell you, don’t write parallel 5ths like you’ll see in the upper bass clarinet) to an A minor chord, and without doing anything, suddenly the marimba’s note is part of the ensemble’s chord. But then the marimba moves down a half-step to B, and it’s out of the chord again. Then it goes to G, also out of the chord, although these are very conservative dissonances. The marimba then begins to repeat those notes while the clarinet chords move down to a root-position E minor chord, then moving up stepwise to an F major chord – but with two notes from the E minor chord held through, resulting in an F major chord with an added 2nd and sharp 4 (the B natural – which also clashes with the marimba’s sustained C). While that chord is sustaining, the marimba changes a note from earlier, going to G# instead of G natural, which clashes pretty badly with the clarinets.

I say it clashes “badly,” but this is relative. If the accompaniment were not using all white-notes (that is, the white keys of a piano), but were more chromatic, the G# might not sound nearly as weird. As it is, though, it’s certainly noticeable that it doesn’t “fit,” but then it resolves to an A in the next bar, and we’re suddenly like, “wait, are we in A minor? I think we’re in A minor now.” (Even without perfect pitch – which I don’t have – when that G# resolves, it feels like it’s established a key of some kind. I think.)

Here’s what the above excerpt sounds like.

[ca_audio url=”https://www.johnmackey.com/audio/Incubate-ex1.mp3″ width=”500″ height=”27″ css_class=”codeart-google-mp3-player”]

And I remember doing none of this. I can look at it and know why I did it, but I don’t know where it came from. One thing I do remember was that I really liked the chord progression. Pretty and simple. I liked it so much that I decided I would repeat it a bunch of times. If you repeat something a lot, it can be called minimalism, or repetitive, or annoying, or ostinato, or lazy, but since I was repeating a chord progression, I decided to consider it a passacaglia. That’s the fancy-pants term for a series of variations over a (mostly repeated) bass line or chord progression, frequently in a triple meter. Some argue that a repeated chord progression (rather than simply a bass line) is a chaconne, not a passacaglia. Since I eventually would vary the chords slightly while maintaining the bass line, I’ll call it a passacaglia. Also, this allows me to share an example of the most famous passacaglia, Bach’s Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor, also as sequenced by me into my Commodore 64 when I was 13 years old. If you thought the earlier prelude was impressive… (If you just listened to the MIDI excerpt above, you should turn your volume down. The Commodore is horrifically loud.)

[ca_audio url=”https://www.johnmackey.com/audio/Passacaglia.mp3″ width=”500″ height=”27″ css_class=”codeart-google-mp3-player”]

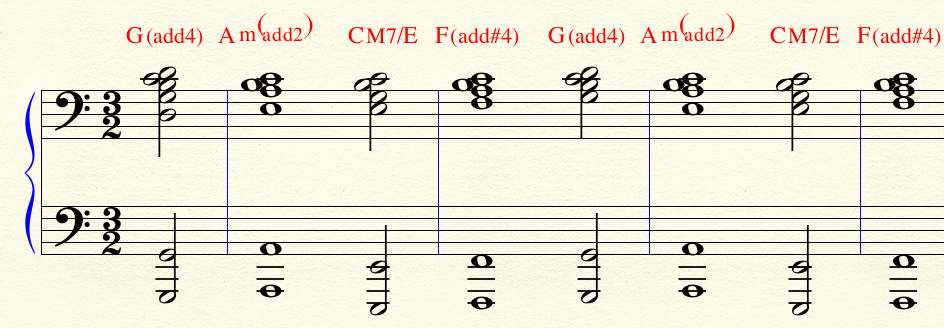

Bach’s progression is 8 bars long. Attention spans have dramatically declined over the past three hundred years, so my progression is two bars, consisting of 4 chords. (Note that it very quickly begins to simply repeat.) There is some variety over the course of the movement (sometimes the Cmaj7/E chord is just an E minor chord, for example), but this is the basic version.

Back to the solo percussion. I’d been writing this thinking it would be on rolled marimba. I wanted to also have bowed vibraphone at the same time, because, well, I love the color of bowed vibe.

Here was my first draft. You can see the bowed vibe above the marimba line.

It sounds like this:

[ca_audio url=”https://www.johnmackey.com/audio/Incubate-ex2.mp3″ width=”500″ height=”27″ css_class=”codeart-google-mp3-player”]

Logistically, this was going to be very difficult. I thought it was reasonable to place a marimba and vibraphone in a way that you could play both at the same time (I’ve heard of this, although I’ve never seen it in person), but with the pedaling required of the vibraphone (if you don’t hold the pedal, the note stops immediately, the same as a piano whenever you release a key), and the reach of the marimba (the instrument is huge), this was going to be a nightmare. Okay, so what if we bowed the marimba instead? According to the Vienna Symphonic Library, if everything were on marimba – the mallet stuff and the bowed stuff – it would sound like this:

[ca_audio url=”https://www.johnmackey.com/audio/Incubate-ex3.mp3″ width=”500″ height=”27″ css_class=”codeart-google-mp3-player”]

Very nice, but a much rounder sound, and I miss the color difference. Bowed vibe, especially with the pedal down, will taper off, but bowed marimba, particularly in this register, just kind of stops. And bowed vibe with the motor on is a great sound. (The vibraphone motor adds what is perceived as vibrato.)

So I kept playing around with the slow-motor vibraphone samples, and I didn’t want to give them up, but I couldn’t have bowed vibes and mallet marimba simultaneously. What if I gave up the marimba instead? Here’s the same excerpt with all vibraphone – one hand plays with two mallets, and the other hand bows the vibes as well.

[ca_audio url=”https://www.johnmackey.com/audio/Incubate-ex4.mp3″ width=”500″ height=”27″ css_class=”codeart-google-mp3-player”]

This sounds to me like a haunted music box. This was the best one yet, and it fixed the issue of “how the hell does the same player play marimba with mallets and bow a vibraphone at the same time.” It also got me away from rolling the marimba constantly, which, frankly, gets pretty old rather fast.

Okay, so we’ve ditched the marimba for this movement, and we just have vibraphone. How should the movement start? (What you see above would eventually start at measure 15.) Because I was enjoying the slow-motor sound, and it’s easiest to hear that effect when it’s alone, let’s start it with a vibraphone solo. And to further embrace this whole “haunted” type thing we were doing, let’s put the pedal to the metal. In other words, we’ll ask that the player hold the pedal down the whole movement, creating a very wet sound, which when combined with the motor-created vibrato, would be exactly the sound I was after. The soloist will start the movement with a cadenza-like solo, in what feels like C minor, making the move to A minor (when the ensemble finally joins in) hopefully feel very satisfying. (I have no justification for why that would be satisfying, other than that I liked it, so that’s what it did.)

But just vibraphone? For the whole movement? That’s not super exciting. I wanted slow and still, but is there a way to make this visceral as well – and maybe visually theatrical? If the ensemble gets loud, we’ll never hear the vibraphone over it. But what would we hear over the ensemble, no matter how loud the passacaglia becomes?

Bass drum. I wanted to have a cadenza at the end of this movement that would lead to the beginning of the final movement, and I’d wanted that cadenza to start on bass drum anyway, so why not introduce the bass drum into the climax of this movement, during the slow, sustained passacaglia?

To summarize, the movement goes like this:

• Solo vibraphone plays an introduction with the slow motor and full pedal

• The ensemble enters with the passacaglia, a simple bass line of G, A, E, F, repeat

• On top of this, the vibraphone “teaches them a song” (to put it the way AEJ described it on first listening)

• The ensemble picks up the song (they’re quick learners), and they take over the melody while the soloist moves to the bass drum. Initially, the bass drum just sneaks in with some rumbling.

• The passacaglia gets bigger. Now it’s C, D, E, F, G, A, repeat. The introduction of the C chord – with all of the contra instruments playing the lowest C in the register – is a needed addition. It makes a big difference when the progression increases in size by 33%. (Insert inappropriate joke here. 33%? That’s nothin’!)

• The passacaglia repeats but continues up the range, so that on the next repeat, it’s an octave higher (starting on the next C). The bottom drops out, and we’re left with that last chord on A, but containing the notes A, B, C, D, E, F, and G (measure 52). This measure alone is the reason why there are 4 flutes and a piccolo in the concerto. Bass drum is no longer happy to be subtle.

• Twice more through the passacaglia, now loud and with the full ensemble, while the soloist plays the hell out of the bass drum – playing from the front of the stage, which should make for a fun visual. (I wanted this concerto to be fun to watch, too.)

• The passacaglia ends, and the soloist begins the improvised cadenza that will lead to movement three,

Incinerate.”

I realize a lot of this is not so much “how it’s made” as, “here’s what I made.” The rest of the details are a blur.

Here’s the link for the full score. “Incubate” begins on page 23. The audio (which is not on the main page for the work) is below.

[ca_audio url=”https://www.johnmackey.com/audio/PercCto-2.mp3″ width=”500″ height=”27″ css_class=”codeart-google-mp3-player”]

September 6, 2011

Drum Music

Last night, after several delays, I finally delivered the materials for my newest piece, a (second) Concerto for Percussion. I wrote a Percussion Concerto back in 2000 for the New York Youth Symphony, and I’ve been asked several times to transcribe it for wind ensemble so that more people could perform it. I never thought that piece would work well with winds, as it’s dependent on slow, long glissandi for the strings in the first movement, and “sawing strings” in the second movement. I was excited about writing a new concerto, though – one specifically for wind ensemble. When Eric Willie and Joseph Hermann from Tennessee Tech University asked me to write a new concerto, I eagerly accepted.

There were a few snags along the way, resulting in a few delays (I was originally supposed to deliver the piece a year ago, and then in March!), but I began working in earnest as soon as we settled at our new house in Cambridge, MA. The commission was for an 8-10 minute “percussion concertino” – a mini-concerto. First I thought I’d do a single large piece with three connected mini-movements – like the Dutilleux Flute Sonatina, a piece that made a huge impact on me when I was young. (I even sequenced that sonatina into my Commodore 64 years ago.)

I got my first piano this summer – I blogged about the Disklavier here – but I’ve barely gotten a chance to play (with) it. So the piano arrived – an instrument I’ve spend literally 20 years wanting – and what’s the first piece I needed to write with it? A percussion concerto. Rather than playing pretty chords (which is about all I can do on a piano, honestly), I found myself mapping the piano’s keys to percussion samples, and entirely running the piano in “silent” mode (where the hammers are disengaged from the strings, but sensors continue to send the key information to the computer). Every once in a while, though, I’d sneak the piano back into, well, piano mode, and play around. I started writing with the piano — i.e., pitched — at night, while I was also writing music for unpitched drums during the day. The result was two rather different kinds of music that turned out to be a little too different on their own to work as a single through-composed 10-minute work. A piece conceived originally as being 10 minutes, with three connected mini-movements, became three big stand-alone movements, and a full concerto of 16 minutes.

The concerto is called Drum Music. The movements are:

I. Infiltrate

II. Incubate

III. Incinerate

In the first movement, Infiltrate, the soloist plays primarily marimba, with a little bit of vibraphone, and a sampling of djembe with hi-hat (to give a little hint of what’s to come later in the concerto). This first movement is really just a lyrical song-like piece, pretty solidly in Mixolydian mode.

The second movement, Incubate, features vibraphone, although the soloist switches – rather dramatically – to concert bass drum towards the end of the movement. This movement was written exclusively “at the piano,” and it sounds like it. The movement ends with an improvised cadenza, starting on bass drum, that transitions directly into the start of the final movement. (I couldn’t figure out how to connect the movements, so I’m making the soloist figure it out.)

The last movement, Incinerate, was written with the piano in “silent” mode, and the sounds of sampled tom-toms and cymbals banging in my ears. Most percussion concerti – at least the ones I know well – seem primarily concerned with proving that “percussionists are not drummers.” Many feature marimba, or are even exclusively marimba concertos (marimba is great in small doses, but I’m not a fan of full-on marimba concertos), and few treat unpitched percussion as something truly bad-ass. It’s like the percussionists asked the composer to show, “no, really, we’re musicians.” Yes, you are, but can we also embrace the fact that playing a solid, heavy groove – with the proper feel and pocket – on drums requires a real musician?

(There are some great percussion concertos out there, of course. The Schwantner is a masterpiece. Higdon’s is incredibly successful as well. But these are few and far between. I’d love to hear the Corigliano some day…)

Whereas my first two movements are fairly intimate in their scoring and feature pitched percussion (marimba and vibes), this last movement has no interest in lyricism, except for a brief quote of a passacaglia that’s originally heard in the second movement. As I wrote on Facebook, “After countless percussion concertos have worked so hard to prove that drummers should be seen as more than just rock stars, I’m pleased to report that the last movement of my piece is going to ruin it for everybody.”

Here is the link for Drum Music, containing a full score, excerpts of the solo part, and the first half of the recording of the final movement (and for the short-term, the complete first movement).

View Comments

Comments

I love the really polyphonic writing you've got going on in the first movement...it sets a great groove.

John,

I'm out of town right now, but as soon as I get back to Tucson, I'm on this hard! I LOVE it. I also like that I'm going to have the opportunity to be a "bad-ass" on the last movement. It's what I was born to do!

That last movement is some good and heavy rock n' roll.

You always set the bar so high and I LOVE that about your percussion writing. I appreciate the e-mail you sent me and I really enjoyed hearing the piece. I'll be keeping an eye out for a possible piano reduction as well as the live recording of the premier.

Wow, the music you've composed is great.

Love the blog and I'm sure the rest of the collective at The Phonography would appreciate this blog too.

Today's article is written by Rowan; an intricate look into the origin of drum beats and Reverse Engineering Breakbeat Culture ...

http://thephonograph.co.uk/2011/09/12/amen-brother-reverse-engineering-breakbeat-culture/

As of today (February 16, 2012) Drum Music: Concerto for Percussion is not on your "Prices" page listing your works and there rental or purchase prices.

I checked the publishers you mention at the footnote on your Prices page but not carry the work.

Is the piece available for rental or purchase for performance? If so, can you direct me (others similarly interested)?

Steven

Add comment

August 14, 2011

Superbike

I recently bought my first new road bike in 10 years. When I lived in NYC, I biked pretty seriously, and whether it meant laps around Central Park (a 6-mile loop with one pretty steep hill – but with the hazards of rollerbladers, unleashed dogs, and unleashed children all along the way); or a 75-mile round trip across the George Washington Bridge, north through Jersey back into New York State, past Nyack, and home again; I loved riding. I even dressed the part.

Then we moved to Los Angeles. Biking in NYC always seemed weirdly safe because there are so many hazards for car drivers that they tend to be pretty aware. It always felt more likely that I’d run over a toddler than get hit by a car. When we got to LA, though, biking felt suicidal. Nobody is watching for pedestrians while they drive, because there are no pedestrians. Nobody walks in LA unless they’re homeless, and biking is even less popular than walking (maybe because the homeless rarely have bikes). So, I stopped biking.

Then we moved to Austin, famous for Lance Armstrong, and thought by many to be cyclist friendly. I’ll admit that I never tested that assumption, but it never seemed safe to me. When a half-dozen deer were killed every season by cars on our residential street — a street with a 30 mph speed limit — that doesn’t say to me “drivers are paying attention.” So, still no biking.

When we moved back to the northeast this summer, I decided that I wanted to ride again. Many people here use bikes as their primary means of transportation, and there are bike lanes on most major roads, so it seemed reasonably safe. (More on that in a minute.) Plus, I missed riding.

I think that if you love road biking, you really love road biking. There isn’t much of an in-between. If you’re willing to wear spandex shorts in public, you probably love road biking. Most people, though, think road biking is ridiculous, with its bent-over posture and clipless pedals. I once told John Corigliano that I’d just finished a 70 mile ride that took about four hours, and he said, “that sounds like a tremendous waste of energy.” But when I’m on a bike, it’s like I’m seven years old again, marveling at the speed I can propel my own body. I’m not good at sports that require hand-eye coordination, but put me on a bike, climbing a hill, and I will crush you, or at least I’ll have fun trying. (But please, don’t expect me to catch a ball. I can bike up a hill because of sheer will, but no amount of will can result in suddenly being able to catch a ball or shoot a basket.)

It turns out that biking in Boston is actually not the safest thing in the world. Less than a week into ownership of my new bike, I was doored. I was riding past my bike shop, so I was going slow, wondering who was working outside, when a car door opened right in front of me. I remember yelling an expletive, but I don’t remember hitting the door. The next thing I knew, I was on the ground, in the middle of the road, thinking, “oh god – my bike, is my bike okay?” while a city garbage truck was hard-braking to avoid running over me.

As luck would have it, the guy who doored me was on his way into the same bike shop, because he’s a bike rep. My front wheel was trashed – spokes everywhere – and my fork was chipped. Other than that, the bike was fine. The guy who doored me – Paul was his name, nice fellow it turns out – offered to cover any expenses associated with the bike. (I’m not sure he realized at that moment how generous this was.) I was moderately banged up, but basically okay, all things considered. It’s weird what shock does to you. All I could think was, “my new bike. Oh god, my new bike,” and it probably took about 15 minutes before the adrenaline started to wear off, and I realized that “holy sh*t… ow.” My right shoulder was scratched, two fingers on my right hand were badly cut, my left elbow was scratched, and my left hip looked (and felt) like I’d been kicked by a horse. I can’t imagine how I managed to bang up both sides of my body, since I literally have no memory of the impact. It’s like my brain said, “hey, we might die right now, and I’m going to channel all of our power into surviving, so I’m going to need to disengage our memory for just a sec.” Anyway, I’m fine, the bike is fixed (new wheel, new fork), and I’m riding a little further from parked cars now.

So, the bike. I figured, if I’m only going to get a new bike once every 10 years, why not go nuts? Full carbon, electronic shifting, total weight: 15 pounds. There will be a lot of nerdy bike details in a moment, and it may not be super exciting if you don’t love road bikes. Hopefully the pictures will be pretty, though.

The bike is the Specialized S-Works Roubaix SL3 Di2. Di2 refers to the Dura Ace Di2 electronic shifting. (The bike lives indoors – but usually downstairs, not next to the bar cart.)

It’s named for the Paris-Roubaix, an annual road bike race in northern France, known for its exceptionally difficult and dangerous conditions, as it goes over many cobblestone sections that are rough, often slick (you should watch this race in the rain sometime), and hell on both the bike and the rider. Specialized designed this bike specifically for the challenges of that race – it needed to be fast, but also forgiving – and for three consecutive years, the winner of that race has won on a Specialized Roubaix just like mine. (That is not the proper front wheel, by the way. I took this picture while I was waiting on my replacement wheel. My bike shop – Ace Wheelworks – can’t say enough good stuff about them, particularly Colin, who fit the bike, and Jerry, who built it – loaned me this wheel while I waited for the replacement.)

The standard wheels are Shimano Dura-Ace tubeless carbon. Carbon is extremely light, and also rides smooth. These tubeless wheels are like car tires, in that (as the name implies) they have no inner tube. Super smooth, quiet, and fast.

Pedals are Speedplay X/1 titanium.

The frame is full carbon.

The shifting is electronic. You still push a button to change gears, but it’s not like a traditional bike, where pushing a lever pulls a cable to change the gear. With electronic shifting, you touch a button – like clicking a mouse – and a small motor changes the gear for you. It changes the gear perfectly every time, and because there’s no cable that can stretch over time, the gears don’t need to be adjusted. Every thousand miles or so, you just need to charge the battery. You can see the battery between the bottle cages. (The bottom bracket uses ceramic bearings, and the crankset is carbon.)

Here’s another shot of the front derailleur. This derailleur, because it’s electronic, will “trim” to match the angle of the chain when you shift to one extreme or the other on the rear derailleur. This means your chain will not rub against the front derailleur if you’re on the big ring in the front, and the left-most gear in the back. It’s pretty sweet to shift the rear derailleur hear the electronic sound of the front derailleur automatically angling itself ever-so-slightly to match.

Here’s the rear derailleur.

A tiny indicator light near the handlebars tells you when it’s time to charge the battery. I’ve had the bike for a month, and even took it on a few heavy-shifting hilly rides in the Berkshire mountains, but haven’t had to charge the battery yet.

A detail shot showing the shifter and brake.

Dura-Ace brakes.

All cabling – brakes and shifting – is internal.

Here’s the saddle that I briefly rode. It was pretty.

Here’s the bike today, now with the correct front wheel. (This is actually the 2012 model of the wheel; the back wheel is the 2011.) You can see that I also have a different saddle now. The last saddle was really uncomfortable. (I don’t like kids *, and don’t want to make any, but I want that choice to be mine, not determined by my bike seat.) This saddle is great, but not as pretty as the old white one. A new white saddle that will fit properly is on the way. Seriously: be sure you have a proper saddle. People often think that they don’t like biking because the seat hurts, but that usually just means you don’t have a good saddle.

* some kids are okay. Amelia Newman is turning out pretty well.

For camera-heads, most of these pictures are from the Canon 50mm f/1.4 lens. That last shot was with the Canon 85mm f/1.2 L II lens. For contrast, here’s a shot at 16mm from the 16-35mm f/2.8 L II – just ’cause it makes the saddle look ridiculously high.

I love this thing. If it were a car, it would be a Tesla Roadster. It is crazy light – 15 pounds! – and so fast and smooth. Riding it feels like riding a bullet over glass. The only thing slowing me down now is my own lack of strength. Oh, and car doors.

View Comments

Comments

Wow, I am jealous. That looks like an incredible bike!

I first got into biking long distances on my grandpa's old bike which he used to deliver mail. When I got a road bike it felt like it weighed nothing... and it weighs at least twice as much as yours.

Do the tubeless tires still get flats? I would love to stop getting flats every few weeks from the random bits of glass which are apparently everywhere out here.

Your memory lapsing at the moment you struck the car door reminds me of an injury I sustained a couple of years ago. There was a really bad ice storm (not as bad as the one a few months back), and as I made my way into the Wal-Mart in town, I slipped and cracked my head on the pavement. How I didn't get a concussion from that is anybody's guess, but I don't really remember hitting the ground. Some cart wrangler saw me fall and said "Oh my god are you all right?"

I lied there for a few moments and said "Boy, I'm glad nobody saw that. That would have been embarrassing."

Thanks for sharing all those awesome bike geek pictures!

I have a real fondness for steel bikes. If money were not an object, I'd have a custom steel bike built for me by a real craftsman. I have one of the last Cannondales made in the United States.

I really want to try the electronic shifters at some point, because they are just freaking cool and the auto-trim thing is sweet.

Mountain bikes are now sporting forks with "brains" that can detect the type of surface you're on and lock out or go squishy accordingly. Bike tech is insane these days.

Do you know bikemep.net?

You can store your route and keep track of your rides.

You might enjoy it.

Here are my routes of this summer:

http://www.bikemap.net/user/cbfr/routes

Nice ride!!! Love the paint job. I MUST have you out next year and find a way to get the machine here also. How do you like the Dura Ace Tubeless Wheels? Getting ready to buy some HED Jet4 soon. Waiting for payment on a new work.

View Comments

Comments

Larry Lawless says

Thank you for putting this up, John. What a great score study and thanks for the insight into "how you think"! I have only recently started keeping multiple Finale files of works in progress for the express purpose of going back and reviewing the process to remind myself, just what the heck was I thinking when I wrote THAT.

- Larry

Steven Bryant says

Great post! Funny, my Piano Concerto (which I just finished, btw), also has a repeated scalar passacaglia-ish bass (throughout first movement) - it must be in the air.

Chris Lexow says

John, it's amazing how you revolve around the idea that composers don't remember their writing. I feel that I'm the same way as well. I JUST finished writing a new piece yesterday, and i'm not entirely sure how I made some of the decisions that I did. Absolutely amazing.

On another note, fantastic writing with the concerto. The section that you present with the vibraphone and your decision to bow and play at the same time is terrific! I feel as though it has hints of Aurora Awakes in them as well ;-)

Fantastic Job!

Marc Bridon says

John, this score study has opened my eyes greatly to the concept of doubling instruments. Being fresh out of college, I didn't quite grasp just how drastically a sound can change with the addition or subtraction of an instrument. My ears weren't quite there yet.

I'll definitely be better attuned to timbre shifts thanks to this.

Sounds great!

Nicholas Hall says

This has been an amazing read about your percussion concerto second movement. I would love to see into your mind on some of your other pieces, maybe asphalt cocktail? (although that would be thinking a few years back).

The bowed and played vibes at the same time is genious, I'm jealous I never thought of that. Also for future referance, to play marimba and vibes at the same time you can put them in an L shape. (the low end of the vibes toughing the high end of the marimba) Depending on where the vibes are placed depends on how low you can reach on the marimba.

I'm very excited to hear a live recording of this work.

Nicolas Farmer says

Wow...

Nice climax! I am anxiously waiting for the live recording... this second movement is going to be the best part!

The first solo vibe part reminds me of exploring a haunted underwater shipwreck by yourself... good job at setting a mood!

NF

Alex Yoder says

I keep listening to this area at 0:28 in the Wiggle Room video - its blowing my freaking mind.

I really like that Incubate movement too. I wanna hear it live.

Andrew Hackard says

I really like reading process pieces from ANY creative folks, and this is among the better ones -- I learned a LOT just reading it.

I do have a question, though; how did you get the C=64 samples up? I've got some files I'd like to bring into the 21st century, but I don't have a computer to do it on.

Add comment