April 7, 2012

Kitties Like Scratchers

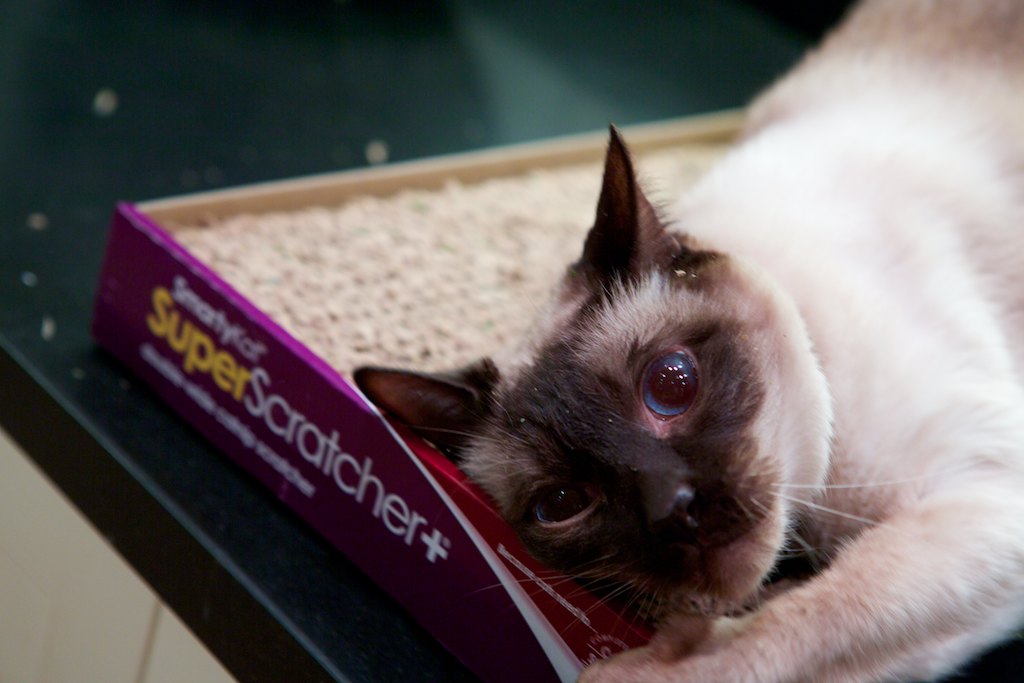

Unlike recent posts about pizza night, or the new program note for “Sheltering Sky,” or the even newer program note for “High Wire,” this post is about one thing: Loki and his new scratcher.

Loki loves it when we get him a new scratcher, and he particularly loves it when it’s covered with fresh (dried) catnip. First, he eats the catnip.

Then, briefly, he sharpens his claws.

And then he starts to get paranoid.

And then he rubs his face all over the scratcher.

And then he gets paranoid again. He doesn’t seem to realize his face is completely covered in weed.

So he does his best to cover his entire body with catnip.

“WHAT THE HELL WAS THAT? Shhh…. Shh shh shh… Can you NOT HEAR THAT?”

Dude.

“Seriously. How can you not hear that?”

Kitties love scratchers.

The end.

April 7, 2012

High Wire program note

Here’s Jake Wallace’s program note for my other new piece, “High Wire” (that link will take you to the page with the score and demo recording), which will receive its premiere next month by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Youth Wind Ensembles.

—

The high wire is a visceral, acrobatic stunt: A tightrope is suspended at enormous height, often swaying above some deadly hazard, and one of the Flying Wallendas dares to traverse it, dazzling the captivated onlookers with death-defying courage and precision. Any errant step brings a gasp of panic from the audience, who dread what they may see yet cannot look away. John Mackey’s High Wire captures that electric sensation, presented without a net above a three-ring heavy-metal circus.

This explosive fanfare courses with dizzying virtuosity – pure kinetic energy released from a compression-loaded spring. The commission — put together by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Youth Wind Ensembles in honor of their founder, Thomas L. Dvorak — was simply for a concert opener but, as Mackey relates, other factors contributed to the eventual composition:

“I was itching to write something fun and flashy and yes — I suppose — virtuosic for the ensemble. I had been writing slow, simple music just before starting High Wire, and my brain felt like a hyperactive dog that’s been locked up indoors for days. I needed to sprint around the yard, musically speaking.

“From the outset, I was just thinking ‘flashy fanfare.’ To me a fanfare is a grand, brass-flourish-loaded opening gesture for a concert, but they’re usually very short. How could I create one that was four minutes long, keeping it exciting while not making it aurally exhausting? I was going for ‘razzmatazz’ and I wanted lots of polychords, plus a largely octatonic scale, but it seems that if I combine those ideas — fanfare plus polychords plus octatonic — we get… circus.”

The octatonic scale Mackey references is a synthetic collection of pitches favored by a host of composers since the beginning twentieth century, including, notably, Igor Stravinsky. This scale works particularly well in High Wire for two reasons. First, it provides a host of semitones, which give any sonority a biting dissonance; and, second, it allows the generation of polychords (two chords that sound like they’re in different keys played at the same time) and quick backflipping between a major and minor “home” key. All of these factors interlaced provide one indisputable characteristic: sonic edge. When applied with bright, pealing orchestration, it presents the listener with a sense of agitation and fright that something might go wrong. That fright comes in waves, as the energies surge, then dissipate, only to reload methodically for another discharge.

Mackey, who makes allusions in his earlier Aurora Awakes to Gustav Holst’s First Suite, slips in a few references to the work here as well. The concluding measures, for instance, mimic the contour of Holst’s thematic motives and orchestration, while a chaconne-like ground bass emerges midway through the work like a troupe of elephants gallivanting about the arena, metamorphosing through its own influence into a demented chorale. This chorale eventually takes over with the force of a rock power modulation and absorbs all of the surrounding virtuosity, pressing down upon the ground before lunging forth one last time and giving the audience a final gasp as the sonic world comes crashing down to the ground around them.

—

And just so this post isn’t only words, here’s a picture I took the other night of arctic char crudo from Rialto.

View Comments

Comments

Add comment

April 4, 2012

Sheltering Sky program note

Jake Wallace has written the program note for my new (and soon-to-premiere) grade 3 piece, “Sheltering Sky.” I expect to have a recording of the piece by the end of the month, and I’ll release the piece in June. Jake’s note is below.

—

The wind band medium has, in the twenty-first century, a host of disparate styles that dominate its texture. At the core of its contemporary development exist a group of composers who dazzle with scintillating and frightening virtuosity. As such, at first listening one might experience John Mackey’s Sheltering Sky as a striking departure. Its serene and simple presentation is a throwback of sorts – a nostalgic portrait of time suspended.

The work itself has a folksong-like quality – intended by the composer – and through this an immediate sense of familiarity emerges. Certainly the repertoire has a long and proud tradition of weaving folk songs into its identity, from the days of Holst and Vaughan Williams to modern treatments by such figures as Donald Grantham and Frank Ticheli. Whereas these composers incorporated extant melodies into their works, however, Mackey takes a play from Percy Grainger. Grainger’s Colonial Song seemingly sets a beautiful folksong melody in an enchanting way (so enchanting, in fact, that he reworked the tune into two other pieces: Australian Up-Country Tune and The Gum-Suckers March). In reality, however, Grainger’s melody was entirely original – his own concoction to express how he felt about his native Australia. Likewise, although the melodies of Sheltering Sky have a recognizable quality (hints of the contours and colors of Danny Boy and Shenandoah are perceptible), the tunes themselves are original to the work, imparting a sense of hazy distance as though they were from a half-remembered dream.

The work unfolds in a sweeping arch structure, with cascading phrases that elide effortlessly. The introduction presents softly articulated harmonies stacking through a surrounding placidity. From there emerge statements of each of the two folksong-like melodies – the call as a sighing descent in solo oboe, and its answer as a hopeful rising line in trumpet. Though the composer’s trademark virtuosity is absent, his harmonic language remains. Mackey avoids traditional triadic sonorities almost exclusively, instead choosing more indistinct chords with diatonic extensions (particularly seventh and ninth chords) that facilitate the hazy sonic world that the piece inhabits. Near cadences, chromatic dissonances fill the narrow spaces in these harmonies, creating an even greater pull toward wistful nostalgia. Each new phrase begins over the resolution of the previous one, creating a sense of motion that never completely stops. The melodies themselves unfold and eventually dissipate until at last the serene introductory material returns – the opening chords finally coming to rest.

—

Thank you, Jake, for yet another great program that makes me look smarter than I am.

View Comments

Comments

TJ says

O, God, please, we need moar of this.

Sarah Sielbeck says

Loki is SO beautiful. Siamese cats are the best. Do you ever need a cat sitter?

Mariko says

I found a cardboard scratcher that's shaped like kind of like an X (but weighted down, like someone tubby sat on top of it), and my two kitties LOVE it. They can sleep on top of it, scratch it underneath in the X's armpits, and army crawl underneath its "legs" to surprise unsuspecting cat toys. Highly recommend!

Jared Mower says

I can't be the only one who thinks this, but I think Loki could make it in the world with his own website. if not then at least post plenty more pictures!!

Add comment